Mamucium c 79 - 400 AD

Genesis of the Romans

Image: Map of the Roman Empire (The Manchester Museum)

At its height the Roman Empire stretched from the Scotland in the north to the edge of the Sahara in North Africa in the south and from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to what is now Iraq in the Middle East. The Romans liked to believe that it was their destiny to rule the world but it was by no means obvious that a modest settlement on the banks of the River Tiber in central Italy would rule all of the lands around the Mediterranean and much of north-western and central Europe. Thanks to the Roman army, which was one of the most efficient fighting forces in the ancient world, and a system of government in which the successful Roman career politician had to be successful militarily in order to hold the highest offices of the state, the Romans expanded their control firstly over Italy and then over much of the western and eastern Mediterranean. In the mid 1st century BC Julius Caesar had conquered Gaul and briefly campaigned in Britain. After a series of civil wars the Roman Republic was overthrown and the Roman Empire founded under the rule of the first emperor Augustus. Members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty – Julius Caesar’s relatives - always regarded Britain was as “unfinished business”.

Roman Manchester

The name Manchester is derived from the name Mamucium or “breast-like hill”. The Romans built a fort on this sandstone bluff overlooking the confluence of the rivers Medlock and Irwell during the governorship of Agricola around AD 79. We know about Agricola because of the biography written by his son-in-law, the Roman historian Tacitus. Agricola seems to have consolidated the Roman advance into the North of England and pushed on into Scotland. The native people who lived in the north were called the Brigantes. A confederation of smaller tribes rather than a single entity, their collective tribal territory stretched from “sea to shining sea” and from the River Don in the south, almost as far as the Scottish borders in the north. Like many other formidable attacking forces, the Roman army was less effective at dealing with guerrilla warfare over mountainous terrain. Units of auxiliaries from the Roman army were used to garrison important locations such as river crossings and valleys in the Pennines, leaving the legions in reserve at Chester and York.

|

|

|

| Images: Roman auxiliary soldier - Rotherham Museum - photo by B.Sitch | Roman legionary - York Museums Trust (Yorkshire Museum) - photo by B.Sitch |

The Strategic Importance of Manchester

Image: Map showing Manchester and other Roman sites in North-West Britain (The Manchester Museum)

The fort at Manchester was sited at an important intersection in the Roman road network in Britain, with roads leading to the legionary bases at Chester (Deva) and York (Eboracum) and up to Hadrian’s Wall via Ribchester. This strategically important location was probably garrisoned initially by a cohort of auxiliaries of the Roman army some 480 men strong. The fort itself consisted of an earthen rampart with defended wooden gateways and towers covering some 3 acres (1.2hectares) at Castlefield at the south end of Deansgate.

The People of Roman Manchester

We do not know precisely which unit held the fort but it is likely the men came from one of the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire. Inscriptions found at Manchester suggest that soldiers from modern Portugal, Spain, Switzerland and Austria either served at Manchester or at nearby places like Melandra or Slack. The movement of people around Europe is no new thing and Manchester was a cosmopolitan place even then!

The auxiliaries were recruited amongst the peoples who had been incorporated within the empire often as a result of war. In return for serving in the Roman army for 25 years the auxiliaries – if they survived – were granted Roman citizenship together with their wives and children. This gave them rights in law not enjoyed by native people. In 1995 remains of a Roman military diploma were found near the site of the Roman fort at Ravenglass and acquired by The Manchester Museum. Although the name of the recipient did not survive there were indications that the man came from Syria originally. On discharge the man chose to remain in Britain rather than return to his home province. It is likely that men from the Manchester garrison made similar decisions and stayed with their wives and children in the civilian settlement outside the fort after they had served their time.

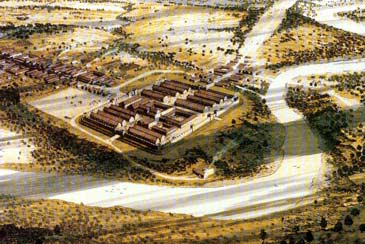

Image: Artist's reconstruction painting showing the Roman fort of Manchester from the west (copyright The Manchester Museum). Note the extensive civilian settlement or vicus (to the left of the fort in this bird's eye view).

Of the native people we know very little either because they were illiterate and did not set up inscriptions or because they rejected the practice altogether. Some must have gravitated towards the fort if only as slaves of the military or as native women who had formed relationships with auxiliary soldiers. By law the soldiers were not allowed to marry but inevitably they had relationships with native women and had children by them. A native woman from the tribe of the Dobunni from what is now Gloucestershire is attested at the Roman fort of Templeborough near Rotherham on the other side of the Pennines. Unfortunately evidence of this kind isn’t available at Manchester because of the intensive development of the fort site and the city centre during the Industrial Revolution.

However, archaeological excavations have shown that outside the fort there was a vicus or civilian settlement, where the dependants of the soldiers and various merchants and traders lived. Evidence of metalworking was widespread, even continuing after the garrison had moved on during the early 2nd century AD.

The Later Earth-and-Timber Fort at Manchester

Unfortunately a large portion of the fort site was destroyed by the cutting of the Rochdale Canal and the building of a railway viaduct and factories during the Industrial Revolution in Manchester in the late 18th and 19th centuries. However, sufficient survived in the north-west corner for archaeologists to excavate and to reconstruct the history of occupation of this important site. Built about 79 AD, the first timber fort was abandoned about 90 AD. Archaeological excavations during the 1970s and 1980s uncovered evidence that the garrison had systematically dismantled and burnt the North Gate and buildings inside the fort before they left. A second timber fort was abandoned in its turn about the middle of the 2nd century AD perhaps because of the re-organisation of troop dispositions prompted by the construction of the Antonine Wall. Some time around 160 AD the Castlefield site was re-occupied by the military and a larger playing card shape fort was built, this time covering some 5 acres (2 hectares). Either there were more men in the new garrison force or perhaps the unit was a part-mounted unit. The stables needed for the horses would account for the larger area occupied by the fort. Unfortunately we do not know for certain which units held the fort at Manchester before the 3rd century AD. Excavations have yielded fragments of tile stamped by the units which made them (XXth Legio XX Valeria Victrix, Cohors IIII Breucorum and Cohors III Bracaugustanorum) but these most likely indicate the supply of building materials from units based elsewhere rather than those units’ actual presence on site.

Images: Portions of tile found re-used in the Roman fort at Manchester made by Legio XX Valeria Victrix and Cohors III Bracaugustanorum.

The Stone Fort

Some fifty years later, in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, the fort was rebuilt in stone. You can see a partial reconstruction of the Roman stone fort at Castlefield complete with a Latin dedication inscription above the gateway. The garrison at this time was a detachment of Raetians and Noricans from what is now Switzerland and Austria. The stone fort may have been occupied almost continuously until the final withdrawal of the Roman army from Britain early in the 5th century AD. Meanwhile houses and shops replaced the extensive industrial activity in the civilian settlement outside the fort. We don’t know what happened after the withdrawal of the garrison but it is likely that many of the inhabitants were the dependents of the soldiers and when the garrison withdrew the civilian settlement went too. Either that or the vicus simply withered away.

Reconstruction of the Latin inscription which may have been set up above the entrance to the stone built fort. Photo: B.Sitch

The consolidated remains of the granary inside the Roman fort. Photo: B.Sitch

Two Roman Altars

Two 2nd century altars from the Castlefield site are now on display in The Manchester Museum. One of them was set up to the goddess Fortuna by a centurion from the Sixth Legion Victrix, which was based in York (Eboracum), in fulfilment of a vow. On the sides of the altar a carved shallow dish and a jug for making liquid offerings or libations can be seen. The altar may have been set up in the vicinity of the baths outside the Roman fort because it was found by the Medlock near Knott Mill. Legionary centurions were sometimes put in charge of detachments such as that recorded in the next inscription.

The second altar was set up by a praepositus or commander of a vexillation or reinforcement of Noricans and Raetians. It has been suggested that this detachment was drawn from soldiers serving with the auxiliaries in Noricum and Raetia and sent to Britain in AD 197 in order to restore order in the province following the Roman civil war, in which the British governor Clodius Albinus had vied with Septimius Severus to become Roman emperor. Albinus was defeated in a battle near Lyons with great loss of life and this detachment of Raetians and Noricans may have been sent by Septimius Severus to reinforce and to help garrison the province.

|

|

|

| Images: Stone altar dedicated by the Lucius Senecianius Martius centurion of the Sixth Legion Victrix (courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum | Stone altar set up by the commander in charge of the Raetians and Noricans (courtesy of the Manchester City Art Gallery) |

The Manchester Word Square

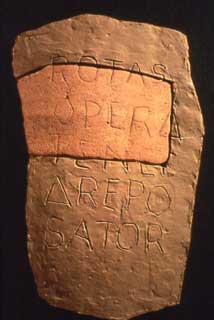

Another exceptionally important discovery also on display at the Manchester Museum.

is an inscribed potsherd from a large wine amphora. It was found was sealed within a dating from about AD 185 outside the Roman fort at Castlefield, Manchester in 1978. It reads: -

ROTAS

OPERA

TENET

AREPO

SATOR

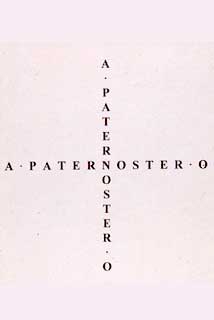

This translates as “The wheels with care guides Arepo the sower” or “Arepo the sower guides the wheels with care”. The letters read in any direction left-to-right, right-to-left, top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top. It is what is known as a palindrome, a puzzle consisting of a square grid to be constructed of words that read the same vertically and horizontally. The Romans appear to have enjoyed puzzles like this but this one may well have special religious significance because the Latin words, when re-arranged read PATERNOSTER or “Our father”, the start of the Lord’s Prayer. It may be a coded message to show membership of a Christian community in Manchester at a time during the later 2nd century AD when Christianity was being persecuted by the Roman authorities. Is it early evidence of Christianity in Roman Britain or is it simply evidence of Roman fascination with word squares, puzzles and brain teasers?

|

|

|

| Image: The Manchester word-square as reconstructed | The expanded form of the Manchester word-square reading PATERNOSTER |

How Will the Romans be Represented at the 7 Ages of Manchester?

Staff members from The Manchester Museum have prepared a short play based on what we know about Roman Manchester to be performed as part of the Seven Ages Festival. You will meet a Roman centurion who has been transferred from York to take charge of the garrison at Manchester. Through him you will find out about the tedium of Roman military life and the unsettled times of the late 2nd century AD. There will be opportunities for the public to meet and talk to the Roman centurion and to take part in his tour of inspection. Have your swagger sticks at the ready!

Manchester Museum is also sending a handling table for members of the public to find out more about Roman Manchester drawing upon the museum’s extensive collection of ancient Roman artefacts and educational materials.

Members of the public can also get involved in similar events at the Manchester Museum as part of National Archaeology Week: -

The Curator of Archaeology at The Manchester Museum, Bryan Sitch, will talk about prehistory and its influence on the Arthurian myths at Café Scientifique, 6.30-8pm, Wednesday 19th July 2006.

There will be celebrations to mark National Archaeology Week at 11am-4pm on Saturday 22nd July 2006 at The Manchester Museum. Come along for a range of handling activities including cleaning a Mesopotamian inscription with the Museum's conservation staff!

Where Can I Find Out More About the Romans?

The Manchester Museum

Find more information here,

or alternatively

http://museum.man.ac.uk